This is the second piece in my series on Solarpunk, so now it’s a trend. (Go read the first post here.) As I explore the Solarpunk aesthetic, I’m writing a weekly post with footnotes (notes, reflections, and recommendations) from my research. If you’re interested in following along, subscribe to get new posts emailed to you.

Nausicaä

In 1984, Hayao Miyazaki released Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. The film was based on a manga series of the same name that Miyazaki had worked on for the previous decade. It’s considered Miyazaki’s breakout feature film and prompted the forming of Studio Ghibli, despite being less famous than others like Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Howl’s Moving Castle. (I haven’t read the Nausicaä manga series, but I plan to—the reviews are astonishingly positive, and it’s supposed to include more world-building and explore more complex themes than the film.)

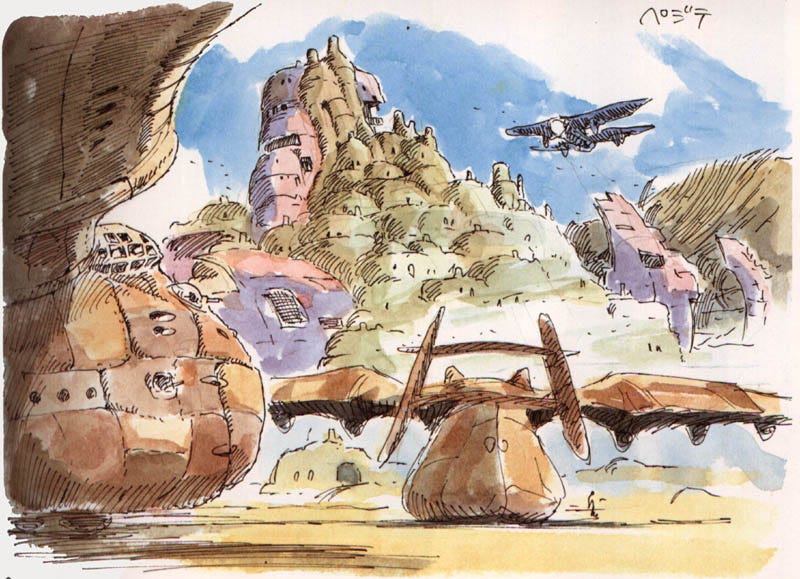

Like many Miyazaki films, this one features a young, female hero (Nausicaä) who saves a post-apocalyptic world from destruction and war. On a purely cosmetic level, this film exudes Solarpunk. Nausicaä’s home (the Valley of the Wind) is an agrarian paradise filled with medieval architecture and futuristic gliders and airships. The mash-up of technologies (like masonry and jet power) is very Solarpunk. (Fun fact: a company in Japan has tried to replicate Nausicaä’s personal glider in real life.)

The story’s setting is a far-future Earth that has been recovering from an apocalyptic event called the Seven Days of Fire that wiped out most of industrial civilization and created an enormous forest called the Toxic Jungle. The jungle is ever-expanding (projected to take over the entire world in a century) and deadly to humans who choke on the infectious spores that grow there. Insects are immune to the spores—and actually spread them—so there’s a world-wide struggle between humans and the forest and its critters.

While many of the remaining human settlements wage war against the jungle, Nausicaä aims to understand and empathize with nature. She possesses a special connection with all living things, and she eventually discovers that the jungle is not the cause of the poison. Instead, human industrialism has polluted the world’s soil. The plants are poisonous because they’re polluted, and actually act as purifying agents, collecting fresh water underground. Nausicaä demonstrates this phenomenon by building a mystical garden of non-poisonous plants using the purified water.

The film is one of the most beautiful pieces of art I’ve seen—it oozes craft from each frame. Miyazaki is also clearly an influence for the Chobani ad from last week’s post. Thematically, the story is optimistic—both about one girl’s ability to affect the world and the root of evil deeds. The wars that play out in the film are waged due to ignorance or fear, not malice. And Nausicaä is able to discover a cure to the struggle through her own exploration and empathy (with other people and the environment), suggesting viewers can do the same in their own worlds.

Nausicaä herself is a compelling Solarpunk example and a hero for the ages. She’s adventurous, kind, empathetic, fierce, capable, curious, formidable, and visionary—similar to Lauren from Octavia Butler’s Earthseed series (see last week’s post). Both protagonists possess a superhuman ability to connect with others. Nausicaä uses a form of telepathy to communicate with animals, plants, and insects, while Lauren was born as a “sharer” (someone in the Earthseed world who experiences the pain and pleasure of others around them). It’s clear that empathy is a pre-requisite for Solarpunk heroes.

Back-to-the-land and All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace

It may seem that applying Solarpunk today would look a lot like back-to-the-land movements of the past, especially homesteading during the Great Depression or communes in the 1970s. Critiquing past efforts and using them to inform a Solarpunk future is an enormous (and daunting) feat, but I’ll include a few initial thoughts today and revisit the topic later on.

There are obvious similarities between Solarpunk tales and the back-to-the-land movements. Especially in the 70’s, large groups of young people migrated out of cities and set up rural communities. They pined for a deeper connection with nature and a return to “basics” in a world dominated by rampant consumerism, the Vietnam War, and political corruption. (Sounds familiar!) Content like Scott and Helen Nearing’s Living the Good Life or the Whole Earth Catalog evangelized the movement and a new lifestyle, as groups learned to build homes, grow their own food, self-govern, and generally sustain themselves without help from the corporate world. (Read We Are As Gods by Kate Daloz for an anecdote of one commune in Vermont.)

There’s something alluring about moving to the countryside with your friends and learning practical skills to survive. But it diverges from Solarpunk in that it seems driven by nostalgia rather than progress. The evidence from back-to-the-land movements of the past suggests that connecting more with the environment means regressing to an earlier, simpler era (like Cottagecore now). And Solarpunk is compelling in part because it embraces nature while still being futuristic.

That’s not to say that the intentions of the back-to-the-land movements weren’t at all futuristic. Here’s one prominent poem from 1967 called All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace by Richard Brautigan:

I like to think (and

the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers

live together in mutually

programming harmony

like pure water

touching clear sky.

I like to think

(right now, please!)

of a cybernetic forest

filled with pines and electronics

where deer stroll peacefully

past computers

as if they were flowers

with spinning blossoms.

I like to think

(it has to be!)

of a cybernetic ecology

where we are free of our labors

and joined back to nature,

returned to our mammal

brothers and sisters,

and all watched over

by machines of loving grace.

The vision here is incredibly high-tech—meadows full of deer and computers and internet-connected trees. The Solarpunk juxtaposition of computers and nature reminds me of Nausicaä exploring the jungle on her glider. I personally would love to spend my days programming out in the forest or sequencing the DNA of my cucumber plants. Though while I’m excited by the first two stanzas, I find the final stanza dystopian and creepy.

But the back-to-the-land movement largely didn’t turn into this cybernetic utopia. Instead, communities found themselves torn apart by financial failure, in-fighting, or other hardships. Re-creating society from scratch and all at once (often without any prior hard skills) is challenging. But not only did very few communes survive, the movement itself didn’t seem to affect the broader political order.

Adam Curtis has a three-part series also called All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace. (It includes this scene of Brautigan reading his own poem, which is worth a watch.) In the second of the three installments, he talks about the back-to-the-land movement, how it was a manifestation of the sorts of thinking represented in Brautigan’s poem, and why it ultimately failed. Here’s an excerpt:

The failure of the commune movement and the fate of the revolutions showed the limitations of the self-organizing model. It cannot deal with the central dynamic forces of human society: politics and power. The hippies took up the idea of the network society because they were disillusioned with politics. They believed that this alternative way of organizing the world was good because it was based on the underlying order of nature. But this was a fantasy. In reality, what they adopted was an idea taken from the cold and logical world of the machines. Now, in our age, we are all disillusioned with politics, and this machine-organizing principle has risen up to become the ideology of our age. And what we are discovering is that if we see ourselves as components in a system, it is very difficult to change the world. It is a very good way of organizing things, even rebellions, but it offers no ideas as to what comes next. And, just like in the communes, it leaves us helpless in the face of those already in power in the world.”

So Curtis’ interpretation is that at a deeper level—below all the trouble of feeding and housing throngs of young people in the countryside—the back-to-the-land movement failed because it wasn’t empowering. Maybe the movement succeeded in creating something akin to Brautigan’s final stanza, removing participants from mainstream society and encouraging them to frolic, unbothered, in nature like other animals. But ultimately that’s not what people wanted.

I’m reminded of Earthseed, the religion Octavia Butler dreams up in Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents. Lauren repeatedly talks about the Destiny of Earthseed (helping humans go to space) and the importance of vision for evangelizing the religion and helping people live purposeful lives. Whatever the Solarpunk equivalent to the back-to-the-land movement is, it should be empowering and enabling of human progress. Forward to the land.

For next week

That’s all for this week. As always, DM me on Twitter if you have Solarpunk thoughts or reading/watching suggestions. Next week I want to talk about victory gardens, Eric Hunting’s incredible Solarpunk essay, and more.