On Solarpunk #8

Small town industry, Arthur Morgan, Mondragon, and climate change

Sometimes I write about Solarpunk science fiction. Other times I share my own original Solarpunk short stories. Today’s post is more historical, but I think you’ll find it’s still thematically Solarpunk. If you want to be notified when I publish new work on this blog, subscribe and add your email below!

People do not live together simply to be together. They live together to do something together.

— José Ortega y Gasset

Last fall, I moved to a new place. My partner and I left San Francisco and drove across the country to the Hudson Valley of New York. We swapped a large West Coast city for a small, rural East Coast town. I have to admit the move was at least somewhat inspired by all the Solarpunk content I’ve consumed this past year. I love that the Hudson Valley is a prime farming zone but is also full of artists, engineers, and everything in between.

Naturally, I’ve been wondering about the future of communities like the Hudson Valley. And I’ve returned to the idea of cosmo-localism, where goods are designed globally and produced locally. I discussed cosmo-localism in On Solarpunk #3 as part of reading Eric Hunting’s Solarpunk essay.

The open source nature of cosmo-localism is novel, but the idea of development via local manufacturing and industry is an old one. Many people have written about local production and its potential benefits, so I’m going to share some of the most meaningful examples from my reading. This post isn’t going to offer a step-by-step guide for small town economic development. Though it should give you a sense for its promise and introduce you to starting points for digging in more.

A library in the Berkshires

My curiosity brought me to the Schumacher Center for New Economics in the Berkshires (Great Barrington, MA to be specific). The organization manages local currency and community land trust projects, and it also hosts the personal library of Ernst F. Schumacher and other intellectuals. Schumacher was an economist who worked with John Maynard Keynes and advised the British National Coal Board. Though he is most famous for his series of essays, Small Is Beautiful, which was first published in 1973. I encourage everyone to visit the Schumacher Center for a day (or many days) of browsing and reading. You can view the library’s catalog online here.

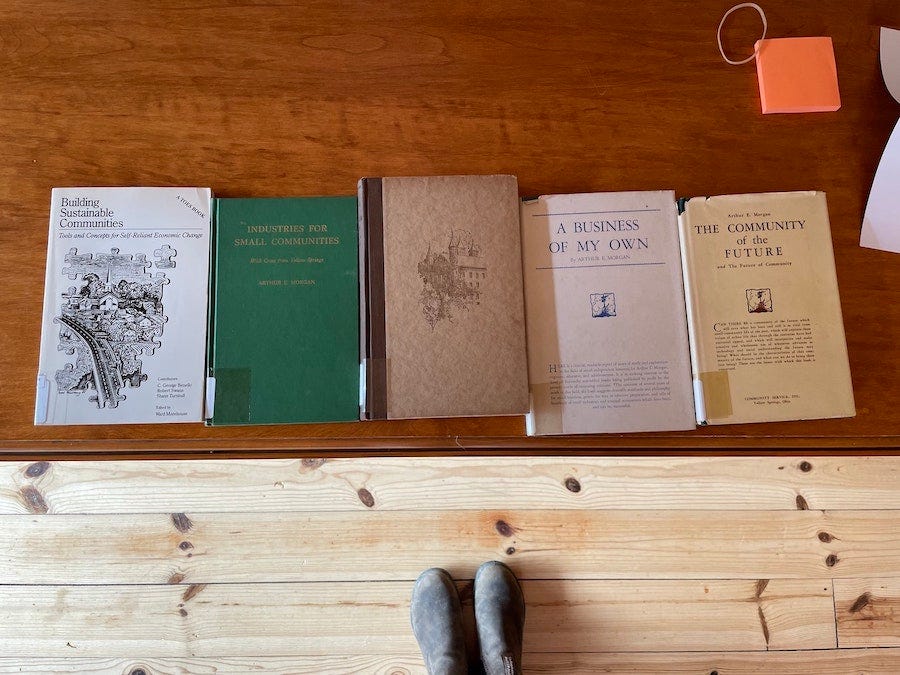

On this particular visit, I was eager to read through the center’s collection of Arthur Morgan books. While they’re difficult to find online, the Schumacher Center has nearly forty books by Morgan—he seemed to be a popular influence for many of the thinkers whose collections are housed at the center. I found three different copies of his book, Industries for Small Communities, for instance.

Arthur Morgan and small town industry

Arthur Morgan was an engineer, President of Antioch College, and one of the first board members of the Tennessee Valley Authority. He was also a utopian thinker (people called him “FDR’s utopian”), and he wrote extensively about community, dam building, industry, and more.

While the Tennessee Valley Authority is extraordinary in scale and ambition, I want to focus on the work Morgan did at Antioch College and the small town it resides in, Yellow Springs, Ohio.

Morgan joined the Antioch College board of trustees in 1919 at a time when the college was near bankruptcy. Even though he was primarily working as an engineer at the time, Morgan wrote a plan for a new curriculum at Antioch that he called “Practical Industrial Education.” It proposed a work-study program, so students would spend as much time learning technical skills in a vocational setting as they did in the classroom. In Industries for Small Communities, he discussed parts of his plan:

Education should concern itself, not with any one or a few phases of living, but with the whole of personality and of life. Every student should have both a liberal and a practical education. His liberal education should not be confined to any segment of culture, such as the humanities or science. Students specializing in the humanities were required to have courses in mathematics, physics, chemistry, geology, biology and psychology, while those specializing in natural sciences were required to take courses in literature, philosophy, and the social sciences. Because one must learn from life as well as from books, a program of alternating work and study was made a part of the new plan.

Antioch College adopted Morgan’s plan and a year later appointed him president. He proceeded to dramatically increase Antioch’s enrollment, faculty, and budget. In order to fulfill his (novel at the time) work-study program, he needed local enterprises to take on students. So they began to create new industries and businesses in Yellow Springs, and Antioch College became an entrepreneurial school.

The book Industries for Small Communities tells the stories of these new businesses, though it was written thirty years after Morgan became president of the college. It’s a great example of successful user research—he goes into great detail describing the origin stories, struggles, and eventual success of these small town enterprises. In the end, the work paid off. Here’s his account of the progress:

A farmer’s village of less than 1500 people, with a very small liberal college, and with almost no industrial life, in the course of two or three decades has become the location of a dozen extremely varied industries, with more than 500 regular employees on its payrolls, and with annual sales of its products of about $7,000,000.

Arthur Morgan wasn’t motivated only by the financial returns of economic development. Both Industries for Small Communities and The Community of the Future and the Future of Community, another book of his written in 1957, demonstrate his small town idealism. He had come to believe that small, rural communities were essential to societal survival and that his experiment in Yellow Springs was part of a greater vision. He wrote:

Throughout human history, and for a long period before that, the small community has been the chief means for transmitting such basic cultural traits as good will, neighborliness and mutual confidence, without which no society can thrive.

His position at Antioch College gave him a chance to demonstrate that a small town like Yellow Springs—and by extension all small towns—could thrive over the long term. The key was to educate young people holistically and create an environment where they had enough volume and variety of fulfilling work to do. If young people consistently left the community in search of broader experience, the community would slowly die. Here’s Morgan talking about retaining young people:

Unless there are reasonable chances for making their livings near home, young people will leave for the city, and with their leaving the home town loses some of its vigor and attractiveness. Nor is it enough that there is a chance to make a living near home. Occupational aptitudes and interests vary widely. Any community with a single economic base, whether it be factory, farming, mining, lumbering, fishing, quarrying, railroading or caring for vacationers, does not offer sufficient range for its young people. Only a minor part of them may be interested in a single local opportunity. If the communities of a region are monotonously alike in their employment opportunities, as sometimes is the case in a farming region, the young people will go where there is greater choice. A young person should not be driven to start another store or filling station, when there are already enough, in order to escape from the one dominant industry and yet remain in the home community. If the home town offers wide occupational choice, and especially if the towns of a locality of considerable variety in their economic activities, young men and women may find at home the work they want, or their movements may largely be back and forth among the towns of the area, and the life and vigor of the region may be well maintained.

But he didn’t believe it was good enough to convince other companies to set up shop in Yellow Springs in order to provide more jobs. He understood that home-grown industry would offer a more fulfilling pursuit and a unique feeling of autonomy and ownership. This passage from Industries for Small Communities is long, but it’s a good summary of Morgan’s overall philosophy:

For persons considering ways to increase industrial life in their communities one general inference might be drawn from the Yellow Springs experience. It is that "man does not live by bread alone." If we could get a true rendering of the rest of that Biblical passage it might be to the effect that man lives by everything that concerns his life and experience. A person considering spending his life in a community is concerned with health conditions, education, cultural and intellectual life, space for children's play and recreation, variety of associations and experience, the character of the people in ethical and spiritual standards, and with opportunities to make a living in ways he can enjoy and respect.

If this is true, then the securing and developing of community industries is not just a matter of getting factories located and under way. It means building a total life and environment in which interesting and competent people will like to participate. It means also achieving human relations in industry such that intelligent and self-respecting employees can feel that they are not just cogs in a machine, but are associates in an undertaking which they can hold in high regard.

That will not be the work of a year, or even of a single decade. If one's life interest is in building a good and enduring community in all of its varied aspects, then the creation of an economic base for community living will have an important place in one's endeavors; but that interest in economic development will be part of a total undertaking, and not an isolated project.

I love this excerpt, and it reminds me of Matthew Crawford’s Shop Class as Soulcraft essay. Twenty years after Morgan, E. F. Schumacher also said something similar in Small Is Beautiful:

We may say, therefore, that modern technology has deprived man of the kind of work that he enjoys most, creative, useful work with hands and brains, and given him plenty of work of a fragmented kind, most of which he does not enjoy at all…we might do well to take stock and reconsider our goals.

I want Morgan to be right about small town industrialism. I want every community to have within it the drive, skill, and creativity to craft meaningful endeavors for its members. I want to believe that “small, independent industries are needed as laboratories and experiment stations in American economic life.” But in today’s globalized, consumer-oriented world, it’s hard to share Morgan’s idealism. Goods today are also far more complex than they were in the 50s, so the sheer breadth of engineering prowess and sophistication required to decentralize industry and produce locally is daunting. Without some intervention that shakes people and causes them to look beyond short-term efficiency, I don’t think Morgan’s ideas will see mainstream success.

The most successful worker co-op in the world

In the Basque region of Spain, a sprawling network of industrial cooperatives is thriving. The network is called Mondragon, and it’s the largest group of worker-owned co-ops in the world.

It was started by the priest, José María Arizmendiarrieta, in 1956. In the wake of the Spanish Civil War, Arizmendiarrieta had founded a technical school in the town of Mondragon. Some of the students from the school started a company making space heaters, and Arizmendiarrieta encouraged them to organize as a worker-owned cooperative after being inspired by the ideas of Robert Owen.

There is a good and short documentary called The Mondragon Experiment that aired in 1980 on BBC, which I also watched during my visit to the Schumacher Center—they have a copy of the original documentary (in VHS). It provides a helpful history of Mondragon and walks through the co-op structure and success. (They also have a copy of We Build the Road As We Travel, a book about Mondragon by Roy Morrison, though I haven’t read that one yet.)

Each Mondragon cooperative is made up of worker-members, and anyone can join by making a capital deposit. That deposit accrues interest over time, and the total can only be retrieved once the worker leaves the co-op or retires.

The majority of co-op profits are also distributed to the worker-members in the form of credit to their deposit accounts. And the remainder of profits are split between community projects (like schools, cultural events, sports venues, etc) and co-op reserves for reinvestment.

For governance, the members elect (one member, one vote) a board of directors and a social council. The board decides on policy and appoints a general manager to run the co-op. And the social council advises the board on wages, worker safety, and related things. Members of the board and social council are not paid extra for their appointments, and each co-op has a maximum wage ratio. The highest paid worker cannot make usually more than 9x what the lowest paid worker does, though the ratio differs co-op by co-op.

Today Mondragon employs over 80,000 people across over 250 businesses and cooperatives, and they make almost $13 billion in revenue per year. You can read their 2020 annual report here. Mondragon has built its own bank, schools, and insurance company, all to support its worker-members. New cooperatives are dreamed up and started by members and funded by the bank. Unemployment is kept incredibly low in the area, because workers are sent back to school if the co-ops don’t have work for them at the moment.

George Benello was a professor and advocate for industrial co-ops who was heavily influenced by Mondragon. (His personal collection, where I found multiple Arthur Morgan books, is also housed at the Schumacher Center.) In an essay called the Challenge of Mondragon he wrote:

Unlike traditional cooperatives, members are considered to be worker-entrepreneurs, whose job is both to assure the efficiency of the enterprise but also to help develop new enterprises. They do this in their deliberative assemblies and also by depositing their surplus in the system's bank, described below, which is then able to use it to capitalize new enterprises. There is a strong commitment on the part of the membership to this expansive principle, and it is recognized that the economic security of each cooperative is dependent on their being part of a larger system.

Sound familiar? It’s similar to Morgan’s emphasis on community members being encouraged to start enterprises together.

Overall, I find Mondragon to be awesome and inspiring. The scale and longevity they’ve achieved is hard to grasp. In fact, when I first read about Mondragon, I believed it was made-up. That’s because Kim Stanley Robinson devotes an entire chapter in his sci-fi book, Ministry for the Future, to the network of co-ops. He seems similarly enamored. Here’s an excerpt:

How this has worked out in Mondragón is open to interpretation. The system has been enmeshed in the world economy all along, and it had to make adjustments when the European Union formed, as well as continuous adaptations to the markets and countries it existed in. There are those who say it could not succeed outside of its Basque context, that Basque culture makes it possible; this seems unlikely, but there are many who don’t want to consider that an alternative to capitalism, more humane, what you might even call a Catholic political economy, not only is possible, but has existed and thrived for a century, and is still going strong.

There have also been moments of crisis, as when recessions struck just at the moment that certain critical cooperatives had expanded, or when a manager absconded with an immense amount of money, causing severe cash flow problems. Still, the place makes a good living for its people, and creates a culture that is mostly loved by those who perform it. There is solidarity and esprit de corps, and even in a world of intense competition, it makes a profit most years, enough for over a hundred thousand people to make a living from it and to give back to the general culture.

So is it possible to replicate Mondragon in many regions around the world? I hope so.

The fact that Mondragon exists gives Arthur Morgan’s ideas more weight, but it’s hard to imagine Mondragon as anything but an extreme outlier. After all, even Yellow Springs hasn’t flourished in nearly the same way. It has just a few hundred more people than it did when Morgan was President of Antioch College, though one of those residents is Dave Chappelle!

Both Mondragon and Yellow Springs are examples of utopian thinkers being in a position where they can apply themselves. And their communities embraced them. Though it’s unclear whether they would have been successful in different circumstances. Yellow Springs was a farming community with a near bankrupt local college, and the town of Mondragon was trying to rebuild itself after the Spanish Civil War. If either community were thriving, maybe they wouldn’t have been open to new ideas.

Both Morgan and Arizmendiarrieta also mixed engineering, philosophy, and education. Arthur Morgan was an engineer who led a college and studied community and psychology. And José María Arizmendiarrieta was a well-read priest who started a technical school. Something special seems to happen when people are exposed to ideas and taught the skills to implement those ideas. E. F. Schumacher has a great quote in Small Is Beautiful about this concept:

When people ask for education…I think what they are really looking for is ideas that would make the world, and their own lives, intelligible to them. When a thing is intelligible you have a sense of participation; when a thing is unintelligible you have a sense of estrangement.

Regardless of the circumstances, community-founded industry flourished in Yellow Springs and Mondragon.

What climate changes

Climate change may cause communities to reconsider local production and their dependence on others. The needs of a community may change due to migration or weather, and it will be much harder or impossible to rely on far-away suppliers. Even now as we try to prevent the worst of climate change, communities have to replace all of their existing fossil fuel-emitting machines with clean, electric ones. We have to decarbonize power generation (solar, wind, nuclear, etc), space heating and cooling (heat pumps), transport (electric vehicles), all kinds of industry, and more.

Forward-thinking communities should look at the changes ahead and see what parts of the future they can provide for themselves (and nearby towns). Can they jumpstart local industry by building batteries or heat pumps? Do members of the community (especially young ones) know how to setup and maintain solar arrays? Can they start businesses recycling refrigerants from old appliances?

A great example of someone already advocating for community resilience and local production is Andy Willner. Andy is based in the Hudson Valley, runs the Center for Post-Carbon Logistics, and has an impressive personal library that he’s put online. He’s written a two-part essay called Rondout Riverport 2040 (Part 1, Part 2). It’s a compelling vision—mixing both analytical argument and climate fiction—for the future of the riverfront where Rondout Creek meets the Hudson River between Esopus and Kingston, NY. He describes a thriving, culturally rich, post-carbon, waterfront industry. Andy’s a great example of someone who understands the potential for small town communities and sees our growing focus on climate as an opportunity to move closer to that ideal.

In his Solarpunk essay, Eric Hunting predicts that communities won’t have a choice. Society will break down, and we’ll have to figure out how to survive with basic technology and local resources—like the settlement of Acorn from Octavia Butler’s world. That’s a bleak yet potentially realistic outlook for the future.

The legacy of Yellow Springs and Mondragon is that there are significant benefits to investing in local industry and resilience. It doesn’t matter whether that investment comes about as a result of crisis or ideology. The communities who figure out how to localize production will be better off and offer a more fulfilling life to their members.

Some Solarpunk tidbits to leave you with

I saw this tweet of Studio Ghibli films recently. I’m a sucker for this aesthetic, even though it may be more Cottagecore than Solarpunk.

Kim Stanley Robinson gave a talk at the Long Now Foundation about his experience at COP26. I encourage any Stan fans out there to watch the full talk, though I particularly appreciated this answer he gave about geoengineering and what it means to be a sci-fi writer.

Here’s a transcript of the answer for those who prefer reading:

We are a technological species. We were technological before we were human. We co-evolved with tools—fire, stones, etc. So maybe this is also part of being a science fiction writer. I believe in technology. But also justice is a technology, language is a technology, it's a big word. It's what we do. And now we're in desperate straights, so I've been thinking: all hands on deck. Really we ought to keep nuclear plants going as a bridge technology to cleaner cleaner. Maybe we might have to do some modifications that people call "geoengineering" (we need to talk about that a little more because there are so many variants going on). But you know me—old hippie…green, eco-marxist, American leftist, although Marxist is really the wrong word…the Wobblies over parties, you know my angle. And from that angle, I say tech, anything, whatever works, except for fascism which wouldn't work anyway. But all of the things we might try, we have to try to see what works and dodge the mass extinction event and then solve the outstanding problems.

One final plug for the Schumacher Center…if you’re a fan of the New Alchemy Institute, you can read the original quarterly reports and journals during a visit. The journals are available online, though it’s fun to flip through the physical copies. Here’s a cover from 1987 that caught my attention.